We don’t often think of Carl Jung as a pioneer in the early integration of Eastern thought, beliefs, stories, and mythologies into the Western intellectual world. While Jung has gained notoriety for his deep knowledge of Western mystical traditions such as Gnosticism and Kabbala, it is less well known that he wrote works relating to Buddhism, Hinduism, and Taoism. In 1929, Jung wrote a psychological commentary in the German edition of an ancient Taoist text, “The Secret of the Golden Flower,” translated from the Chinese by Richard Wilhelm. The work appeared a few years later in English: "The relation of the West to Eastern thought is a highly paradoxical and confusing one. On the one side, as Jung points out, the East creeps in among us by the back door of the unconscious, and strongly influences us in perverted forms, and on the other we repel it with violent prejudice as concerned with a fine-spun metaphysics that is poisonous to the scientific mind. A partial realization of what is going on in this direction, together with the Westerner's native ignorance and mistrust of the world of inner experience, build up the prejudice against the reality of Eastern wisdom. When the wisdom of the Chinese is laid before a Westerner, he is very likely to ask with a skeptical lift of the brows why such profound wisdom did not save China from its present horrors. … Through the combined efforts of Wilhelm and Jung we have for the first time a way of understanding and appreciating Eastern wisdom which satisfies all sides of our minds. It has been taken out of metaphysics and placed in psychological experience. … this book not only gives us a new approach to the East, it also strengthens the point of view evolving in the West with respect to the psyche. … In the commentary [Jung] has shown the profound psychological development resulting from the right relationship to the forces within the psyche" (Translator‘s Preface, by Cary F. Baynes, p. vii-ix, Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co. (London): 1931). Jung’s ideas on Eastern thought catapulted themselves into the very heart of Western academia, perhaps even leading to an invitation by Yale University in 1937 to deliver the famous Terry Lectures “Lectures on Religion in the Light of Science and Philosophy.” Yale also honored Jung with an honorary doctorate. In my opinion, Jung would go further than any intellectual before him to integrate ideas triggered by Eastern thought-motifs into his works, which were primarily intended for Westerners. The collision of Jung and East brought him beyond writing with a focus only of an individual or personal conception of the personality. Jung conceived of a collective unconscious – a reservoir of human experience that occurs semper ubique, Latin for “always and everywhere” meaning that recorded history documents similar experiences in all time eras in across the globe. Jung’s interest in Eastern thought appears vividly in his investigation of the mandala, one of the sacred symbols in Buddhism and throughout the East. Mandala means a “circle,” more especially a magic circle. Mandalas appear in the West during the early Middle Ages of the Christian era. Jung’s psychological innovation was identifying the mandala with an activation of the self, what he calls the center of the entire personality, as distinguished from the ego, which is the center of consciousness. For more on Jung and East, read four articles that we are posting until the end of March, 2013. After that time, they will be available for reading in our Library.

0 Comments

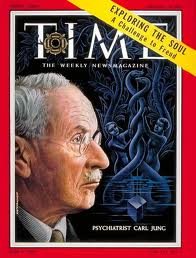

Jung's "Psychological Interpretation of Children's Dreams" was delivered as a course at the Eidgenossische Technische Hochschule in Zurich, Switzerland in 1938-39. [Read an Excerpt on our website.] "The dream is, as you know, a natural phenomenon. It arises from no conscious effort. It cannot be explained by a psychology which is based on consciousness only. It ... is quite independent of the will or desire, or of the intentions of aims of the human ego. It is an unintentional happening, like all the events in nature. ... The difficulty lies in understanding this natural phenomenon" (p. 2). RIW: What does Jung mean when he calls a dream a "natural phenomenon"? A dream may be considered like other bodily functions, perhaps even as the "output" of one of its "organs." For just as the heart, being the "pump" of the circulatory system, has its output of blood, an "output" of the seele [Ger. for soul or mind] is the dream. I hold that underneath conscious activity, the dream (or what Hillman calls "imagining") continuously occurs. When the tension of consciousness reduces, as during normal sleep or in pathology (e.g. Alzheimer's) or injury (coma or altered consciousness from toxins or injury) can one become aware of the activity of these visual images. It is during REM sleep with its associated brain wave activity that we become the dream state occurs. When we awaken, the ego, which never completely fades from functioning, even in sleep, is able to remember the autonomously produced imaginal activity from sleep. Dreams being ubiquitous to humankind clearly must relate to a natural functioning of the body. Beside the metabolic necessity of dreams, they have something to do with the imaginal matrix from which consciousness arises, the visual language that precedes auditory language. Jungian analysts hold that dreams reveal the creative and emotive forces that drive behavior as well as showing the counterpoint (i.e. compensation and complementary contents) of consciousness in symbolic form. "Whatever we have to say about [dreams] must be acknowledged as our own interpretation. ... We are confronted by the difficult task of translating natural processes into psychical language. ... Whatever meaning one ascribes to [dream] events, [it] must always remain a human assumption, and nevertheless, [one should] attempt to comprehend the underlying primary facts. One is never absolutely certain whether one is reaching this goal, but the uncertainty is partially overcome [as one] ... observes ... [the dream] offers an intelligent solution" (p. 2). RIW: Underlying Jung's words are his practice to first allow oneself to be moved by the imagery of our dreams. To "feel" a dream first gives back to its contents some of the original intensity they possessed while unconscious. One then amplifies the dream's motifs using both personal associations and parallel material from humankind's common experience. Lastly, comes interpretation, our own sense of what the dream means to us. An intelligent and sound scientific approach to the dream uses hypothesis, meaning that one's idea of a dream's meaning should always be kept flexible, waiting for the next alternative way of understanding it. This is the healthy "modicum of doubt" that Jung always taught his students to hold. 8/28/2012 0 Comments Review of "Two Essays on Analytical Psychology" 1928 Translation by Carl Gustav Jung Amazon Reviews by Robert Winer, M.D. "Two Essays on Analytical Psychology" 1928 Translation by Carl Gustav Jung First English Language Translation of Jung's Two Essays This is the Baynes translation. In my opinion, Baynes, a medical doctor, analytical psychologist who trained under Jung, gives a translations that has quite a different feel from the Collected Works of Jung (translator most of the volumes is Hull). Hull wasn't a medical doctor and so, though his knowledge of Jung was encyclopedic, lacked the clinical feel that is retained in the Baynes translation. So my suggestion, particularly for all who maintain a clinical practice and want to incorporate Jung's ideas into their practice or for all Jungian analysts or trainees, is that this book is a must have for your library and education.  Carl Gustav Jung was a human-enigma, even to himself. During the last 6 years of his life he described himself as “complicated phenomenon.” A razor-sharp intellectual, innovative theorist, and high-profile psychoanalyst whose work bi-directionally resonates through the corridors of time, history, and myth. Simultaneously, with a feature article entitled "Medicine: The Old Wise Man" and his picture being on the cover of Time Magazine (February 14, 1955 Vol. LXV No. 7), some people condemned him as womanizer, recluse, and even anti-Semite; he is a figure that has been a focal point of controversy both during his life and long-after. Jung was born on July 26, 1875 in Kesswil, Switzerland, a town of mostly fisherman and farmers. Jung was the only surviving child of Paul Jung, a Protestant minister, and Emilie Preiswerk. The Preiswerks were Swiss citizens related to the vom Tieg, an ancient royal family from Basel, while the Jung’s were Germans exiles whose ancestry included a later conversion from Roman Catholic to Protestant in the 1700's. At the tender age of four years old the Jung family moved to Basel; soon after, Paul began teaching his son Latin. Carl’s gift for language would prove lasting; he would eventually master a variety, including English, French, ancient Greek, and Sanksrit. Jung was an introverted child possessed of great intelligence. In other words, Carl was a walking bull’s-eye for any playground bully. Indeed, while attending a boarding school in Basel, his classmates tormented the timid Jung who typically played alone. In Deirdre Bair's book "Jung: A Biography," she writes the “... parents of the village children deliberately kept them away from the odd little boy, whose parents were so peculiar” (p. 22). After matriculating from the Humanistisches Gymnasium, the bullying Jung endured culminated in a traumatic incident when, at age 12, a classmate shoved him so hard he was knocked unconscious. Carl began to faint frequently for years afterward and later described the experience as a childhood neurosis. Jung’s grandfather had been a professor of surgery at the University of Basel. Despite C. G. Jung’s first inclination toward a career in archeology, the very realistic young man realized that such a profession would never provide him the job and financial security he needed. Jung eventually picked medicine at the University of Basel which included both an M.D. degree and a doctorate allowing him to be accepted as an academic with the title of Privat-docent in Psychiatry at the University of Zurich (Dissertation, “On the Psychology and Pathology of So-Called Occult Phenomena”. Jung’s most significant mentorship came after he graduated, taking he took a staff position at the Burghölzli Mental Hospital in Zurich under the tutelage of Eugen Bleuler. There he also achieved world acclaim as research scientist in Psychiatry performing pioneering studies on the Word Association Test. |

On Smartphones, click on the above form and enter your blog in the "COMMENT" section.

Archives

June 2014

CategoriesAll Child Psychology Consciousness Development Dreams Ego Fixation Freud Fromm Hillman Hyperactivity Incest Individuation Intellect Jung Books Articles Mandala Self Spirit Taoism The Four Functions Unconscious Visions Seminar Word Association Test Working With Images |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed