|

6/11/2014 0 Comments Primal desire for mother love / protection and Primal fear: mother as the devourer, which can be a realistic fearErich Fromm writes in "The Heart of Man": The incestuous tie to mother very frequently implies not only a longing for mother's love and protection, but also a fear of her. This fear is first of all the result of the very dependency which weakens the person's own sense of strength and independence; it can also be the fear of the very tendencies which we find in the case of deep regression: that of being the suckling or of returning to mother's womb. These very wishes transform the mother into a dangerous cannibal, or an all-destroying monster. It must be added, however, that very frequently such fears are not primarily the result of a person's regressive fantasies, but are caused by the fact that the mother is in reality a cannibalistic, vampire-like, or necrophilic person. If a son or a daughter of such a mother grows up without breaking the ties to her, then he or she cannot escape from suffering intense fears of being eaten up or destroyed by mother. The only course which in such cases can cure the fears that may drive a person to the border of insanity is the capacity to cut the tie with mother. But the fear which is engendered in such a relationship is at the same time the reason why it is so difficult for a person to cut the umbilical cord. Inasmuch as a person remains caught in this dependency, his own independence, freedom, and responsibility are weakened. Fromm points out an important psychological truth: in the unconscious and, yet, well-meaning pursuit for healing love and protection (mature eros), one may “find” a personal “mother” figure or a collective “mother-substitute” who are “in reality … cannibalistic, vampire-like, or necrophilic” [1] What Fromm seems to mean here is that such an imago as understood from the subject's dreams, nightmares, or visional experiences, are not only “regressive fantasy” (à la Freud) but typically in their totality also represent some kernel of a truth about the actuality of the suffer's problem or situation.

Fromm’s important observation of this “objective side” [2] of a personal or institutional neurotic split [3] typically plays out in unconscious manifestation of the power instinct: actions on the part of the “mother” figure or institution to control, or if that is not possible to devour and destroy the “rebellious” one. [4] In my clinical work, this “script” frequently plays out in actuality in the lives of many young adults. Fromm’s advice — to “cut the tie with the mother” — often takes the support of an outside person (a counsel, pastor, rabbi, therapist) who loans the patient their own experiences of courage with an attitude of non-judgmental support until their own efforts to gain greater freedom, independence, and adult responsibility become manifested in their behavior and in confronting the more problematic actualities of life. 1 For more on Fromm’s meaning of this term, see Chapter III “Love of Death and Love of Life” in The Heart of Man. 2 I use this term psychologically to help the reader distinguish it from another categorial term referring to the “personal” or “subjective” aspect of any psychological framework. 3 Yes, sadly, I do mean that there are “neurotic” institutions which are in reality more destructive, immature, and even “toxic” than being constructive, mature, or nurturing. 4 Strong language, but the use of the term “rebellious” characterizes the conscious or unconscious frame shown by the behavior: the actions, decisions, or explicit standpoint of a particular personal mother figure or institution. Copyright 2014, Robert Winer, M.D. (May not be used without permission).

0 Comments

5/2/2014 1 Comment NarcissismToday, I re-read the following section from p. 77 of Erich Fromm's book "The Heart of Man." In this book, a sequel to the "The Art of Loving" he deals with the opposite trait from "love" (which was the topic of "The Art of Loving") — the destructive instinct that instead of loving life — takes it apart — and so, affirms "death" rather than life.

This instinct has been rather consistently operating in Western society. And especially since Luther and the Reformation has been unconsciously blending itself with Protestant Christianity (in its Triumphalist versions), our attitudes toward the industrial and technological revolutions, and our unreflected ideas about development, growth, and progress. In this segment of the book he is talking about individuals who exhibit narcissistic attitudes, traits, and personalities. Benign and malignant narcissism In discussing the pathology of narcissism it is important to distinguish between two forms of narcissism — one benign, the other malignant. In the benign form, the object of narcissism is the result of a person's effort. Thus, for instance, a person may have a narcissistic pride in his work as a carpenter, as a scientist, or as a farmer. Inasmuch as the object of his narcissism is something he has to work for, his exclusive interest in what is his work and his achievement is constantly balanced by his interest in the process of work itself, and the material he is working with. The dynamics of this benign narcissism thus are self-checking. The energy which propels the work is, to a large extent, of a narcissistic nature, but the very fact that the work itself makes it necessary to be related to reality, constantly curbs the narcissism and keeps it within bounds. This mechanism may explain why we find so many narcissistic people who are at the same time highly creative. In the case of malignant narcissism, the object of narcissism is not anything the person does or produces, but something he has; for instance, his body, his looks, his health, his wealth, etc. The malignant nature of this type of narcissism lies in the fact that it lacks the corrective element which we find in the benign form. If I am “great” because of some quality I have, and not because of something I achieve, I do not need to be related to anybody or anything; I need not make any effort. In maintaining the picture of my greatness I remove myself more and more from reality and I have to increase the narcissistic charge in order to be better protected from the danger that my narcissistically inflated ego might be revealed as the product of my empty imagination. Malignant narcissism, thus, is not self-limiting, and in consequence it is crudely solipsistic as well as xenophobic. One who has learned to achieve cannot help acknowledging that others have achieved similar things in similar ways — even if his narcissism may persuade him that his own achievement is greater than that of others. One who has achieved nothing will find it difficult to appreciate the achievements of others, and thus he will be forced to isolate himself increasingly in narcissistic splendor. 4/21/2014 0 Comments The unconscious as "inside"Freud and others have shown that there's an "inside" to actions, feelings, motivation, and thinking. No one can seriously doubt that this is so. However, since then being that we have rightly used the term "unconscious" as an adjective put before these nouns, some have inadvertently made a valuable concept into something like a definite fact. To my mind, this well-proven inference – that there is an "inside" – becomes confused with fact, because now there is 1) knowledge about the different ways in which these phenomena of behavior and symptom manifest and also 2) these rhetorical forms have led to the discovery of therapies that may be used to clinical benefit. Review of Elain Pagel's book "Adam, Eve, and the Serpent: Sex and Politics in Early Christianity"

March 2, 2014 By Robert Winer, M.D. "@robertwinermd" To See Review on Amazon.com "Super book for anyone interested in how the doctrine of Original Sin arose and how Jewish exegesis turned into the Catholic mode," In 1989, when this book was published, Pagels was the Professor of Religion at Princeton University. In my estimation, I consider her more of a religious historian than a theological religionist. So her book provides a clear historical account of how the doctrine of original sin arose from the first century through the time of Augustine. She shows how the Christian perspective on free will, sexual issues, and marriage changed over time and how this, along with the Romanization of Christianity (the merger of Church and State) changed and affected the biblical exegesis. Also for those interested in an understanding of the Jewish roots of Christianity, the chapter on the first century points out some very interesting statements, such as the assertion that in the first century, the Jewish moral standpoint was toward multiple marriages. So she suggest that some establishment Jewish religionists used their exegesis of Genesis 1-3 (really what she means is their interpretation, read, on twist on the narrative of Adam, Eve, and the Serpent in Genesis to support their position on the issue. A very quick read. Today, we had a very nice web-based discussion on Lecture One of Jung's 1935 lecture series called the Tavistock. We only got to paragraph eight of the first lecture.

There will be other opportunities if you missed it. I will make the URL for the meeting permanent at: http://fuze.me/18408927 DAY OF WEEK: I will pick a weekday late morning, or lunch time US TIME: Probably to begin at 11:30 AM, 12 NOON, or 12:30 PM Mountain Standard Time (Colorado) That way my UK, European, Eastern European, South African, and Middle Eastern friends can conveniently join us: In the meantime, I'll keep LECTURE 1 posted on line at: http://www.jungboulder.org/education.html or buy the book locally or through Amazon (prob. < $10.00 USD) http://www.amazon.com/Analytical-Psychology-Practice-Tavistock-Lectures/dp/0394708628 Watch for notices on: FB Twitter @jungboulder and @robertwinermd Linkedin feed if you are "friends" with me Wordpress: http://rwinermd.wordpress.com/ Tumblr: http://www.tumblr.com/blog/rwinermd Web @ www.jungboulder.org and http://rwinermd.com 1/31/2014 0 Comments What is Perception?I consider perception as sensation plus meaning — already a mixture of more than one function. Thus to me, perception describes a complex mode of human functioning in which an individual pays attention to certain stimuli arising from the sense organs or brain and ignores other ones, regardless of whether the paid-attention-to arises through sensation or intuition as understood through the Jungian or Myers-Briggs grid. As I conceive it, human perception presupposes a considerable amount of unconscious ordering and rejection prior to its awareness.

"Dictionary of Analytical Psychology" – Copyright 2006-2014 Robert Winer, M.D. Version Date: 01/31/2014 NYTimes.com http://nyti.ms/1lLgcx7 SCIENCE | THE MAPMAKERS By JAMES GORMAN JAN. 6, 2014 ST. LOUIS — Deanna Barch talks fast, as if she doesn’t want to waste any time getting to the task at hand, which is substantial. She is one of the researchers here at Washington University working on the first interactive wiring diagram of the living, working human brain. To build this diagram she and her colleagues are doing brain scans and cognitive, psychological, physical and genetic assessments of 1,200 volunteers. They are more than a third of the way through collecting information. Then comes the processing of data, incorporating it into a three-dimensional, interactive map of the healthy human brain showing structure and function, with detail to one and a half cubic millimeters, or less than 0.0001 cubic inches. Dr. Barch is explaining the dimensions of the task, and the reasons for undertaking it, as she stands in a small room, where multiple monitors are set in front of a window that looks onto an adjoining room with an M.R.I. machine, in the psychology building. She asks a research assistant to bring up an image. “It’s all there,” she says, reassuring a reporter who has just emerged from the machine, and whose brain is on display. And so it is, as far as the parts are concerned: cortex, amygdala, hippocampus and all the other regions and subregions, where memories, fear, speech and calculation occur. But this is just a first go-round. It is a static image, in black and white. There are hours of scans and tests yet to do, though the reporter is doing only a demonstration and not completing the full routine. Each of the 1,200 subjects whose brain data will form the final database will spend a good 10 hours over two days being scanned and doing other tests. The scientists and technicians will then spend at least another 10 hours analyzing and storing each person’s data to build something that neuroscience does not yet have: a baseline database for structure and activity in a healthy brain that can be cross-referenced with personality traits, cognitive skills and genetics. And it will be online, in an interactive map available to all. Dr. Helen Mayberg, a doctor and researcher at the Emory University School of Medicine, who has used M.R.I. research to guide her development of a treatment for depression with deep brain stimulation, a technique that involves surgery to implant a pacemaker-like device in the brain, is one of the many scientists who could use this sort of database to guide her research. With it, she said, she can ask, “how is this really critical node connected” to other parts of the brain, information that will inform future research and surgery. The database and brain map are a part of the Human Connectome Project, a roughly $40 million five-year effort supported by the National Institutes of Health. It consists of two consortiums: a collaboration among Harvard, Massachusetts General Hospital and U.C.L.A. to improve M.R.I. technology and the $30 million project Dr. Barch is part of, involving Washington University, the University of Minnesota and the University of Oxford. Dr. Barch is a psychologist by training and inclination who has concentrated on neuroscience because of the desire to understand severe mental illness. Her role in the project has been in putting together the battery of cognitive and psychological tests that go along with the scans, and overseeing their administration. This is the information that will give depth and significance to the images. She said the central question the data might help answer was, “How do differences between you and me, and how our brains are wired up, relate to differences in our behaviors, our thoughts, our emotions, our feelings, our experiences?” And, she added, “Does that help us understand how disorders of connectivity, or disorders of wiring, contribute to or cause neurological problems and psychiatric problems?” The Human Connectome Project is one of a growing number of large, collaborative information-gathering efforts that signal a new level of excitement in neuroscience, as rapid technological advances seem to be bringing the dream of figuring out the human brain into the realm of reality. Worldwide Study In Europe, the Human Brain Project has been promised $1 billion for computer modeling of the human brain. In the United States last year, President Obama announced an initiative to push brain research forward by concentrating first on developing new technologies. This so-called Grand Challenge has been promised $100 million of financing for the first year of what is anticipated to be a decade-long push. The money appears to be real, but it may come from existing budgets, and not from any increase for the federal agencies involved. A vast amount of research is already going on — so much that the neuroscience landscape is almost as difficult to encompass as the brain itself. The National Institutes of Health alone spends $5.5 billion a year on neuroscience, much of it directed toward research on diseases like Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s. A variety of private institutes emphasize basic research that may not have any immediate payoff. For instance, at the Allen Institute for Brain Science in Seattle, Janelia Farm in Virginia, part of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, and at numerous universities, researchers are trying to understand how neurons compute — what the brains of mice, flies and human beings do with their information. The Allen Institute is now spending $60 million a year and Janelia Farm about $30 million a year on brain research. The Kavli Foundation has committed $4 million a year for 10 years, and the Salk Institute in San Diego plans to spend a total of $28 million on new neuroscience research. And there are others in the U.S. and abroad. To be sure, this is not the first time such a focus has been placed on brain research. The 1990s were anointed the decade of the brain by President George H. W. Bush. Strides were made, but many aspects of the brain have remained mysterious. There is, however, a good reason for the current excitement, and that is accelerating technological change that the most sanguine of brain mappers compare to the growing ability to sequence DNA that led to the Human Genome Project.

“There is an explosion of new techniques,” said Dr. R. Clay Reid, a senior investigator at the Allen Institute, who recently moved there from Harvard Medical School. “And the end isn’t really in sight,” said Dr. Reid, who is taking advantage of just about every new technology imaginable in his quest to decipher the part of the mouse brain devoted to vision. Charting the Brain Of the many metaphors used for exploring and understanding the brain, mapping is probably the most durable, perhaps because maps are so familiar and understandable. “A century ago, brain maps were like 16th-century maps of the Earth’s surface,” said David Van Essen, who is in charge of the Connectome effort at Washington University, where Dr. Barch works. Much was unknown or mislabeled. “Now our characterizations are more like an 18th-century map.” The continents, mountain ranges and rivers are getting more clearly defined. His hope, he said, is that the Human Connectome Project will be a step toward vaulting through the 19th and 20th centuries and reaching something more like Google Maps, which is interactive and has many layers. Researchers may not be looking for the best sushi restaurants or how to get from one side of Los Angeles to the other while avoiding traffic, but they will eventually be looking for traffic flow, particularly popular routes for information, and matching traffic patterns to the tasks the brain is doing. They will also be asking how differences in the construction of the pathways that make up the brain’s roads relate to differences in behavior, intelligence, emotion and genetics. The power of computers and mathematical tools devised for analyzing vast amounts of data made such maps possible. The gathering tool of choice at Washington University is an M.R.I. machine customized at the University of Minnesota. An M.R.I. machine creates a magnetic field surrounding the body part to be scanned, and sends radio waves into the body. Unlike X-rays, which are known to pose some dangers, M.R.I. scans are considered to be safe. It is one of the few methods of noninvasive scanning that can survey a whole human brain. There are a variety of ways to gather and interpret information in an M.R.I. machine. And different types of scans can show both basic structure and activity. When a volunteer is trying to solve a memory problem, the hippocampus, the amygdala and the prefrontal cortex are all going to be involved. An M.R.I. The many folds and valleys of a single brain surface, left, and a composite image using data from 12 subjects, right, suggest the degree of variation in human brains. M. F. Glasser and D.C. Van Essen for the WU-Minn HCP Consortiummachine can detect the direction of information flow, in a technique called diffusion imaging. In that kind of scan, the movement of water molecules shows not only activity, but which way the traffic is headed. A Path to Research For Dr. Barch, 48, another kind of interest in the human brain put her on the path to Washington University. “I always knew I wanted to be a psychologist,” she said — specifically, a school psychologist. But as an undergraduate at Northwestern, she excelled in an abnormal psychology class, and the professor recruited her to do research. “When I graduated from college, I decided to become a case manager for the chronically mentally ill for a year to kind of suss out, ‘Do I want to do more clinical work or research?’ ” she said. “That was a great experience, but it really made me realize that research is the only way you’re going to have an impact on many lives, rather than sort of individual lives.” She obtained her Ph.D. in clinical psychology at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. but then did postdoctoral study in cognitive neuroscience at the University of Pittsburgh and Carnegie Mellon University. Her years in graduate school in the 1990s coincided with the development and use of the so- called functional M.R.I., which can show not just static structure, but the brain in action. “I got into the field when functional imaging was just at its very beginning, so I was able to learn on the ground floor,” she said. She moved to Washington University after her postdoctoral research partly because of the number of people there working on imaging, including Dr. Marcus E. Raichle, a pioneer in developing ways of watching the brain at work.

For instance she said, people doing memory tasks in the M.R.I. machine may differ in competitiveness and commitment to doing well. That ought to show up in activity in the parts of the brain that involve emotion, like the amygdala. However, she points out that the object of the Connectome Project is not to find the answers to these questions, but to provide the database for others to try to do so. ‘Pretty Close’ The project at Washington University requires exhaustive scans of 1,200 healthy people, age 22 to 35, each of whom spends about four hours over two days lying in the noisy, claustrophobia-inducing cylinder of a customized M.R.I. machine. Sometimes they stare at one spot, curl their toes or move their fingers. They might play gambling games, or try memory tests that can flummox even the sharpest minds. “In an ideal world, we would have enough tasks to activate every part of the brain,” she said. “We got pretty close. We’re not perfect, but pretty close." Over the two days, the research subjects spend another six hours taking other tests designed to measure intelligence, basic physical fitness, tasting ability and their emotional state. The volunteers (and they are all volunteers, paid a flat $400 for their time and effort) can also be seen in street clothes, doing a kind of race around two traffic cones in the sunlit corridor of the glass-walled psychology building, with data collected on how quickly they complete the course. Or they can be glimpsed padding down a hallway in their stocking feet from the M.R.I. machine to an office where a technician dabs their tongues with a swab dipped in a mystery liquid, then asks them to identify the intensity and quality of the taste. In the same office, they type in answers to cognitive tests, and to a psychological survey, for which they are left in solitude because of the personal nature of some of the questions: how they feel about life, how often they are sad. The results are confidential, as are all the test results. So far almost 500 subjects have gone through the full range of tests, which amounts to about 5,000 hours of work for Dr. Barch and others in the program. So far, data has been released for 238 subjects, and it is available to everyone for free through a web-based database and software program called Workbench. The sharing of data is characteristic of most of the new brain research efforts, and particularly important to Dr. Barch. “The amount of time and energy we’re spending collecting this data, there’s no possible way any one research group could ever use it to the extent that justifies the cost,” she said. “But letting everybody use it — great!” The Elusive Brain No one expects the brain to yield its secrets quickly or easily. Neuroscientists are fond of deflecting hope even as they point to potential success. Science may come to understand neurons, brain regions, connections, make progress on Parkinson’s. Alzheimer’s or depression, and even decipher the code or codes the brain uses to send and store information. But, as any neuroscientist sooner or later cautions in discussing the prospects for breakthroughs, we are not going to “solve the brain” anytime soon — not going to explain consciousness, the self, the precise mechanisms that produce a poem. Perhaps the greatest challenge is that the brain functions and can be viewed at so many levels, from a detail of a synapse to brain regions trillions of times larger. There are electrical impulses to study, biochemistry, physical structure, networks at every level and between levels. And there are more than 40,000 scientists worldwide trying to figure it out. This is not a case of an elephant examined by 40,000 blindfolded experts, each of whom comes to a different conclusion about what it is they are touching. Everyone knows the object of study is the brain. The difficulty of comprehending the brain may be more aptly compared to a poem by Wallace Stevens, “13 Ways of Looking at a Blackbird.” Each way of looking, not looking, or just being in the presence of the blackbird reveals something about it, but only something. Each way of looking at the brain reveals ever more astonishing secrets, but the full and complete picture of the human brain is still out of reach. There is no need, no intention and perhaps no chance, of ever “solving” a poet’s blackbird. It is hard to imagine a poet wanting such a thing. But science, by its nature, pursues synthesis, diagrams, maps — a grip on the mechanism of the thing. We may not solve the brain any time soon, but someday achieving such a solution, at least in scientific terms, is the fervent hope of neuroscience. A version of this article appears in print on January 7, 2014, on page D1 of the New York edition with the headline: The Brain, in Exquisite Detail. © 2014 The New York Times Company Sociopathy / Psychopathy

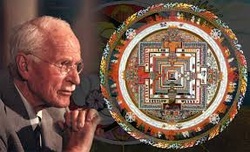

Click on the following: Psychopathy: an Audio Discussion taking place at the University of Pennsylvania. Brief Review by Robert Winer, M.D. Brain imaging "shows" that murders have less well functioning or working pre-frontal cortex, (PFC) which controls the more aggressive limbic system. All brain imaging work is correlational. Neurologists who performed selective lesions of ventro-medial PFC were able to demonstrate blunted emotional response, disinhibited, etc. in the subjects. Current studies use the term "fear conditioning" to describe the so-called normal ability to predict in childhood that certain stimuli predictable result in punishments and that the thought of these punishments or the actual punishments are associated with feelings of anxiety and nervousness. This researcher defines conscience as "a set of classically-conditioned emotional responses, coming from the ability in childhood to associate stimuli that reliably predict punishments". What he means is that when, in childhood, you broke a rule it was predictably followed by punishments.  We don’t often think of Carl Jung as a pioneer in the early integration of Eastern thought, beliefs, stories, and mythologies into the Western intellectual world. While Jung has gained notoriety for his deep knowledge of Western mystical traditions such as Gnosticism and Kabbala, it is less well known that he wrote works relating to Buddhism, Hinduism, and Taoism. In 1929, Jung wrote a psychological commentary in the German edition of an ancient Taoist text, “The Secret of the Golden Flower,” translated from the Chinese by Richard Wilhelm. The work appeared a few years later in English: "The relation of the West to Eastern thought is a highly paradoxical and confusing one. On the one side, as Jung points out, the East creeps in among us by the back door of the unconscious, and strongly influences us in perverted forms, and on the other we repel it with violent prejudice as concerned with a fine-spun metaphysics that is poisonous to the scientific mind. A partial realization of what is going on in this direction, together with the Westerner's native ignorance and mistrust of the world of inner experience, build up the prejudice against the reality of Eastern wisdom. When the wisdom of the Chinese is laid before a Westerner, he is very likely to ask with a skeptical lift of the brows why such profound wisdom did not save China from its present horrors. … Through the combined efforts of Wilhelm and Jung we have for the first time a way of understanding and appreciating Eastern wisdom which satisfies all sides of our minds. It has been taken out of metaphysics and placed in psychological experience. … this book not only gives us a new approach to the East, it also strengthens the point of view evolving in the West with respect to the psyche. … In the commentary [Jung] has shown the profound psychological development resulting from the right relationship to the forces within the psyche" (Translator‘s Preface, by Cary F. Baynes, p. vii-ix, Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co. (London): 1931). Jung’s ideas on Eastern thought catapulted themselves into the very heart of Western academia, perhaps even leading to an invitation by Yale University in 1937 to deliver the famous Terry Lectures “Lectures on Religion in the Light of Science and Philosophy.” Yale also honored Jung with an honorary doctorate. In my opinion, Jung would go further than any intellectual before him to integrate ideas triggered by Eastern thought-motifs into his works, which were primarily intended for Westerners. The collision of Jung and East brought him beyond writing with a focus only of an individual or personal conception of the personality. Jung conceived of a collective unconscious – a reservoir of human experience that occurs semper ubique, Latin for “always and everywhere” meaning that recorded history documents similar experiences in all time eras in across the globe. Jung’s interest in Eastern thought appears vividly in his investigation of the mandala, one of the sacred symbols in Buddhism and throughout the East. Mandala means a “circle,” more especially a magic circle. Mandalas appear in the West during the early Middle Ages of the Christian era. Jung’s psychological innovation was identifying the mandala with an activation of the self, what he calls the center of the entire personality, as distinguished from the ego, which is the center of consciousness. For more on Jung and East, read four articles that we are posting until the end of March, 2013. After that time, they will be available for reading in our Library. Troubled Children: Living With Love, Chaos and Haley

When Haley Abaspour started seeing things that were not there — bugs and mice crawling on her parents’ bed, imaginary friends sitting next to her on the couch, dead people at a church that housed her preschool — her parents were unsure what to think. After all, she was a little girl. “I thought for a long time, ‘She’s just gifted,’ ” said her father, Bejan Abaspour. “ ‘This is good. Don’t worry about it.’ ” But as Haley got older, things got worse. She developed tics — dolphin squeaks, throat-clearing, clenching her face and body as if moving her bowels. She heard voices, banging, cymbals in her head. She became anxiety-ridden over run-of-the-mill things: ambulance sirens, train rides. Her mood switched suddenly from excitedly chatty to inconsolably distraught. “It’s like watching ‘The Sound of Music’ and ‘The Exorcist’ all at the same time,” Mr. Abaspour said. For her family, life with Haley, now 10, has been a turbulent stream of symptoms, diagnoses, medications, unrealized expectations. Diagnosed as a combination of bipolar disorder with psychotic features, obsessive-compulsive disorder, generalized anxiety disorder and Tourette’s syndrome, her illness dominates every moment, every relationship, every decision. Haley’s fears, moods and obsessions seep into her family’s most pedestrian routines — dinnertime, bedtime, getting ready for school. Excruciating worries permeate her parents’ sleep; unanswerable questions end in frustrated hopes. “The first time we took Haley to the hospital, I guess I expected that they would put it all back together,” said her mother, Christine Abaspour. “But it’s never all back together.” At least six million American children have difficulties that are diagnosed as serious mental disorders, according to government surveys — a number that has tripled since the early 1990’s. Most are treated with psychiatric medications and therapy. The children sometimes attend special schools. But while these measures can help, they often do not help enough, and the families of such children are left on their own to sort through a cacophony of conflicting advice. The illness, and sometimes the treatment, can strain marriages, jobs, finances. Parents must monitor medications, navigate therapy sessions, arrange special school services. Some families must switch neighborhoods or schools to escape unhealthy situations or to find support and services. Some keep friends and relatives away. Parents can feel guilt, anger, helplessness. Siblings can feel neglected, resentful or pressure to be problem-free themselves. “It kind of ricochets to other family members,” said Dr. Robert L. Hendren, president-elect of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. “I see so many parents who just hurt badly for their children and then, in a sense, start hurting for themselves.” Ms. Abaspour, 39, struggles to master the details of Haley’s illness, to answer her obsessive questions, to keep her occupied. Mr. Abaspour, 50, who long believed that “Haley was going to grow out of it,” has been gripped by anxious thoughts and intrusive images that rattle him to tears on the hourlong commute to his job as an anesthesia engineer at a Boston hospital. He imagines people being crushed by trucks, someone hurting Haley, his own death. Haley’s sister, Megan, 13, has been so focused on Haley and determined not to add to her family’s burden that in June, after a quarrel with her parents, she tied a T-shirt around her neck in a suicidal gesture. “I feel like she gets all the problems and I feel like I have to take some of that off of her,” Megan said. “It’s really difficult a lot to try to stay away from babying her and helping her. I try to stay still but it just hurts, it hurts inside.” Haley, with her shy smile and obsidian eyes, is increasingly aware of her own problems, although she cannot always express exactly what is going on inside. “My mind says I need some help” is the way she explained it recently. Her illness has caused great financial strain; although the Abaspours have health insurance, they have been forced to draw on their savings and lean heavily on their credit cards for living expenses. Still, they have bought a trailer in a New Hampshire campground because there Haley finds occasional solace, and relatives nearby understand the family’s ordeal. The family wrestles with deciding whom to tell about Haley’s illness, and what to say. Her worst symptoms are most visible at home and less apparent at the public school and the state-financed therapeutic after-school program she attends. Her parents say she works hard to hold herself together during the day and then later, feeling more comfortable with her family, falls apart. This disparity in behavior is not uncommon, said Dr. Joseph A. Jackson IV, Haley’s psychiatrist, and “parents often get the brunt.” Because of the contrast in Haley’s public and private behavior, her parents are wary of telling people that she is mentally ill, as they might not notice. “I don’t want anybody to pity her,” Mr. Abaspour said. But they also get frustrated when teachers or relatives play down the seriousness of Haley’s illness, or conclude that she is being manipulative or that another child-rearing approach would help. In the middle of last year, for example, a teacher did not understand Haley’s need to leave the classroom to quiet the voices or relieve anxiety. Haley grew so frustrated that she “would sit there in her chair and cry,” her father said. The parents pressed school officials to switch her to another class. “We’re sick and tired of trying to prove it to people,” Ms. Abaspour said. Her husband added, “Everybody thinks they have the solution. When Joe Schmo comes over for a drink, he says, ‘Try this, this will work.’ No, it won’t.” Visions and Voices From birth, it was clear that “I was dealing with something different,” Ms. Abaspour said. Displaying a photo album with picture after picture of Megan all smiles and Haley “crying, crying, crying,” she added, “We just thought we had a very difficult child.” Yet exactly what was wrong puzzled them for years, and even now, Ms. Abaspour said, “Every day it’s something new, I swear.” While increasing awareness of childhood mental illness has helped many children and families, it can also create a misimpression that everything can be treated, said Dr. Glen R. Elliott, chief psychiatrist at the Children’s Health Council, a community mental health service in Palo Alto, Calif., and the author of “Medicating Young Minds: How to Know if Psychiatric Drugs Will Help or Hurt Your Child.” That can make families with complex cases feel “either genuine confusion or pretend certainty,” Dr. Elliott said. The Abaspours decided to speak with a reporter about Haley’s illness and its impact on their family because they hoped it would help other families and make society more hospitable for children like their daughter. Talking about it was sometimes emotional, especially for Mr. Abaspour, whose eyes often clouded with tears. But they also said they found it useful to articulate their feelings. When Haley was 3 or 4, a pediatrician blamed tonsillitis-induced sleep apnea, predicting that after her tonsils were removed, “ ‘you’ll see a totally different child,’ ” Ms. Abaspour recalled. “We thought, ‘This is what is wrong with our child. This is our answer,’ ” she said. Preschool teachers suggested a learning disability. Later, Haley repeated first grade. The Abaspours consulted therapists about the visions of friends in the liner of the family’s pool and riding with Haley on her bike, and the voices criticizing her or telling her to touch a certain table. When a neurologist ruled out medical causes like Lyme disease, Ms. Abaspour recalled, her husband said, “I think we should just give her a placebo — it’s all in her head.” They got a cat, “though we weren’t cat people,” Ms. Abaspour said. Then they got another because the first was “not the type of cat that Haley could throw over her shoulder and squeeze.” New symptoms kept emerging. For a while, when she was about 7, the voices “were telling her she was a boy,” Ms. Abaspour said. “She had to constantly prove to them that she wasn’t.” Haley became obsessed with penises, which she called “bums.” She claimed to see them though she was looking at fully clothed men and boys, her mother said. “Then she felt guilty. She would come up to me and whisper, ‘I saw his bum, I saw his bum.’ The bus driver or the little boy, anyone. It was constant.” To halt the whispering, Ms. Abaspour suggested that they share a private signal: Haley could flash a thumbs-up after a sighting. Haley also seemed preoccupied with death, and on a highway would say that voices told her, “If that license plate didn’t say such and such, she was going to die,” her mother said. Once, Mr. Abaspour recalled, Haley “kept yelling that she wants to start over.” The Treatment Puzzle When she was almost 8, Haley visited Dr. Jackson at his office at the Cambridge Health Alliance. He was struck by the results of a screening: Haley met full criteria for virtually every mental disorder listed. “Her symptoms,” he said, “suggested anxiety, morbid thoughts, obsessions possibly of a sexual nature, frequent fluctuations in mood, periods of euphoria, giddiness, irritability, rapid speech, auditory and visual hallucinations, thought disorganization, vocal tics, distractibility, poor socialization in school, sensory integration issues, attention impulse disorder, manic behavior, sleep disturbance.” Dr. Jackson wondered if the voices and the friends, which Haley told him were “nowhere but everywhere,” were schizophrenic-like hallucinations or milder thought distortions. He also saw Haley’s mood swing from anxiety about a “disturbing dream in which her mother was killed” to euphoria, as she gleefully drew a large, brightly colored butterfly and a self-portrait with a too-big smile and a skirt that ballooned as if she were floating. The pictures, he said, “scream” manic sensibility, suggesting bipolar disorder. Dr. Jackson prescribed an antipsychotic, Risperdal, one of a dozen drugs Haley would try. Some helped initially, but the voices returned or side effects developed. Huge pills or bad-tasting liquid made Haley gag or throw fits. “It was horrible, horrible, horrible,” her mother said, “and she’d pull us into it because we had to make her take it.” Lithium caused weight gain: clothes that fit her one day no longer did the next. When Haley was 81/2, Mr. Abaspour said, “Let’s drop all of these medications and see what happens.” He said, “I wanted to see her true self.” The results chastened them. “You see her fine one day,” Mr. Abaspour said. “The second day comes and she’s fine and you say, ‘You see, honey, there’s nothing wrong with her.’ Then it’s the third day and she goes crazy and you feel like an idiot.” Haley resumed taking Risperdal. Then, abruptly, her condition worsened. “She couldn’t function, she couldn’t go to school,” said Ms. Abaspour, who took Haley to a hospital; she had to handle the crisis with her husband away in London. In the emergency room, Haley was manic and hyperarticulate, Ms. Abaspour recalled. “I was a basket case.” When Mr. Abaspour returned and saw Haley “like a zombie” in a hospital full of out-of-control children, his first reaction was, “She can’t be in here.” But the eight-day hospital stay made him grasp the severity of her illness. “You look at an X-ray and you say it’s a fracture,” he said. “But this thing. ... Before then, there wasn’t solid evidence.” A year later, school halls “would get scary because the voices would get louder,” so Haley constantly visited the school’s nurse and psychologist, her mother said. “She was going out of her mind.” Haley was hospitalized again, and another antipsychotic drug, Abilify, muffled the voices. “I remember thinking, ‘Am I supposed to be happy about this?,’ ” Ms. Abaspour said. She was grateful that something helped but distressed at the suggestion that Haley was psychotic. The Abilify has not soothed Haley’s anxiety or stopped her outbursts. And despite increases in the dosage, back are the voices (four boys and a girl), the tics (eye squinting and hand clenching) and the “bums.” Dr. Jackson, her psychiatrist, said Haley’s biggest asset was her “very caring family” that was “seeking ways to shore themselves up” to better help her. Ms. Abaspour said: “We ask ourselves sometimes, ‘Why? Why did it happen to us?’ Other times we see a child bald, going through chemotherapy. That’s the thing about this — it’s on the inside, you can’t see it.” Megan’s Heartache I pretend no one is around me when my sister is there. I feel a constant hurt inside. I touch a rainbow of joyfulness in my mind when my sister and I are FINALLY having a fun laugh together. I worry that when one day I die, I won’t be there to help my sister. I cry to the stars, pleading them to take me away from this madness at mind. Megan’s sixth-grade writing assignment was to write a poem called “I Am.” Virtually every line was about Haley. Megan wrote of love, frustration, obligation, pain, embarrassment. Eighteen months later, those feelings erupted. Told to do dishes before calling a friend, Megan felt that the chore should be Haley’s and stormed to her room. When her father said it was Megan’s responsibility, “I really got mad and slammed the door,” she recalled. “He came and ripped my phone right out of the wall.” That was unusual for Mr. Abaspour, usually gentle or quietly humorous. “I tried not to say something that would hurt her,” he said. “And definitely not to touch her. So I took it out on the phone.” Megan said her reaction was, “Why should I live?” “I took a T-shirt and I put it around my neck,” she said. “Then I said, ‘No I shouldn’t do this. I want to live but I don’t know another way out.’ ” Siblings of mentally ill children often have such feelings, experts said. Ten days of treatment helped Megan understand that “I felt pretty much like I was another mom for Haley,” she said. The Abaspours, who always gave Megan positive attention, were stunned. But Ms. Abaspour said she might have unconsciously been relieved that Megan could get Haley to laugh, or in other ways “take a little attention off me.” For Megan, a doctor prescribed Prozac, but she became edgy and the suicidal thoughts continued. “When I’m doing dishes and I see a knife there, my mind’s like, ‘Pick up the knife and kill yourself,’ ” Megan said. “I kind of just think, ‘Would things be easier without me?’ ” Now she has stopped taking medication and is seeing a psychiatrist. Her parents are encouraging her to focus more on herself. She realizes, she said, “I’m important.” Still, trying not to help Haley is hard. “I don’t really feel the pain that she feels,” Megan said, “but I feel that I should to make it even between us.” Haley’s mother calls it “the ongoing search” — Haley’s obsessive quest for novelty and for objects to hold or to stroke over her touch-sensitive skin. “I need something to calm me down so I can learn how to end my frustration,” Haley said. “I just get, like, sometimes, mad. I need to, like, hold it or hug it or just play with it.” She and her family search through stores, scavenge through her crawlspace storage area and her bedroom full of Beanie Babies, toy cars, dolls. Megan said she sometimes offered her own belongings for Haley, thinking, “if I get excited about it she’ll decide it’s the right thing.” But, Ms. Abaspour said, “she’s never satisfied.” Because her parents sometimes brush the hair on her arm with a surgical brush from Mr. Abaspour’s hospital, the family’s therapist recently suggested getting a soft lambskin. Haley fixated on buying one, always asking as if it were a new thought: “Oh my God, you know what just came to mind? If I get that animal fur...” Megan found her a faux shearling vest to stroke instead, but Haley exploded. “I wanted Megan to find something like that animal fur,” she wailed, convulsing and weeping. Anguished as he watched her, Mr. Abaspour said: “This is the point of no return. She’ll scream and cry and kick. If the neighbors could hear, they would think we were abusing the kid.” Haley refuses to be consoled or touched, all the while saying, “Please help me, please make it stop, please make it go away,” her mother said. The Abaspours look on helplessly or send her to another room. Haley’s eruptions, often 20 minutes long, occur almost daily, especially in the evenings. They often begin with Haley revved up. Before the lambskin incident, for example, she marched around, chatting giddily about camp: “Today, today, today, we, um, instead of two periods of the game thingies, they call it sessions, periods, each session or whatever, we went to the picnic tables and we all went to the picnic tables and it was really fun.” Haley’s parents struggled to track her unspooling sentences and scrambled thoughts. “Did you follow the bouncing ball?” Ms. Abaspour asked her husband, who replied, “I don’t even see the ball, honey.” Haley sighs, frowns and fidgets, eyes drooping before she falls apart. Sometimes she hyperventilates or crawls under a table. It always ends with crying, but sometimes she will start to laugh through her tears, becoming “all chipper again, like manic,” Mr. Abaspour said. Adds Ms. Abaspour: Later, “she says, ‘I’m sorry, I’m sorry,’ apologizing for who she is.” Her father said: “It’s not like a hurt that you can kiss better. It comes from within, and she doesn’t know why, and you can’t do anything about it.” A Mother’s Stoicism Christine Abaspour, the youngest of four girls raised by a divorced mother, knew what she wanted early in life. At 19, she left Massachusetts, joined a sister in Florida and became a waitress. At 25, she met her husband-to-be, who was 11 years older. She was engaged in two weeks, married in nine months and a mother a year later. “We both wanted to have children right away, like you wouldn’t believe,” she recalled. Ms. Abaspour said that she had no regrets, and that Haley “was given to us for some reason, and I keep waiting for the day when I realize why.” Still, the experience has tested her stamina, and she avoids capitulating to Haley’s whims and outbursts by imposing structure, consistency, even distance. “I’m her mother,” Ms. Abaspour said. “I try to make it a better world for her, a more comfortable world. I stay very strong for her and very encouraging for her. If she comes out of a meltdown, I’ll say, ‘I knew that you could.’ I don’t make her feel totally hopeless. It doesn’t give me any satisfaction, though, because I still feel helpless. Unfortunately it just bites you in the face all day long.” Ms. Abaspour’s stoic approach, which her husband appreciates but cannot always emulate, is “a good coping skill for parents,” Dr. Elliott, of the Children’s Health Council, said. “It’s what happens to a family system when you’ve got a source of chaos in the middle of it.” After getting Haley ready for school, Ms. Abaspour feels she has already lived an entire day. In the afternoon, “Haley walks in the door and I just want to hold her and give her a big kiss like most kids,” Ms. Abaspour said. “Instead I get a frown and tears and ‘Ooh, I had such a stressful day.’ ” She said that every evening, a distraught Haley will “say to me her same 12 questions: ‘What’s going to happen when I need to go to school and I can’t leave the classroom?’ or ‘What do I have to look forward to today?’ ” By bedtime, Ms. Abaspour said, “your heart’s just breaking.” To slake Haley’s thirst for “something to do,” Ms. Abaspour keeps her involved in activities outside of school. Otherwise, the family ends up stopping for ice cream or concocting other outings, because unstructured time allows Haley to focus on the voices and anxiety. “Staying home is not an option,” Ms. Abaspour said. “Honestly I could not keep her busy. Sometimes being around here on a Saturday or Sunday, it’s almost toxic. She has multiple episodes — it’s like living hell.” Haley’s fears of noises, crowded streets and surprises force the Abaspours to forgo amusement parks, apple picking or other traditional family activities. When relatives visit “and you think it’s going to be relaxing and we’ll watch movies and eat popcorn — that doesn’t happen in this family,” Ms. Abaspour said. Instead, there are mood cycles, as when Haley marched around announcing, “I’m going to make a really great art project,” then fell apart, wailing, “I don’t know what to do.” Ms. Abaspour stays unflustered. When Haley bawled, “I don’t have any markers,” her mother replied, “Oh, don’t tell me you don’t have.” But she found Haley a T-shirt to cut up and draw on, saying, “If I can get her to do that kind of chop, chop, chop, mark, mark, mark, it kind of brings her back.” Ms. Abaspour said she had watched “everyone else in the family rush over to her, and I won’t become a part of that. I make her be responsible for her own feelings because I can’t be responsible for those. You still have to be a regular parent. Honestly, she has to learn to soothe herself.” But Ms. Abaspour doggedly monitors Haley’s progress. This summer, she visited Haley at day camp and was dismayed that the child frequently declined to participate, asking for the nurse. Sitting out the swim period one day, Haley, wearing a “Keep It Cool” T-shirt, listed her feelings on a worksheet: “stressed, axxouis, sick, shacky.” At lunch, she mostly licked salt off pretzels. Asked to choose a word-card matching her emotions, she picked “overwhelmed.” Ms. Abaspour worries that as Haley becomes a teenager, her poor social skills might get her “mixed up with the wrong kids” or lead her to use illegal drugs. So she arranges play dates, but if friends are unavailable “it’s the end of the world,” she said. If they are available, she said, Haley anxiously asks, “What do I say, Mommy?” Ms. Abaspour was recently laid off from a medical assistant’s job. Her former co-workers understood her need to interrupt work to deal with Haley’s needs, she said, and “didn’t look at me and say, ‘Her child’s crazy.’ ” Now she fears she will not find an employer who is as tolerant, though the family needs the income. Haley’s illness, the Abaspours were dismayed to discover, does not qualify for disability assistance. In August, Ms. Abaspour arranged an elaborate 50th-birthday surprise party for her husband. They were “not always on the same page” about Haley at first, she said, but their strong marriage helps her handle the strain. So do bright spots, she said, like the day Haley “really kissed me.” Still, she can get overwhelmed. Sometimes she bolts awake at night, but she declines medication. “I can’t climb in a shell and stay there forever,” she said, “although it seems like some days where I’d want to be.” A Father’s Anxiety As a young man, Bejan Abaspour worried, especially about family. Twenty years ago, for example, when his sister’s son was born, “I pictured my nephew getting Super Glue in his eyes and I was calling my sister saying, ‘Make sure you keep Super Glue away from him.’ ” But the worries were not that intense — until Haley’s illness. After that, the intrusive thoughts and images got worse, horrific scenes in which he imagines himself as bystander or thwarted rescuer. “I’ll be driving next to a semi tractor-trailer truck and all of a sudden I will picture someone getting crushed by the wheel,” he said. “It’s usually an older lady or a kid. You get them out from under the truck, but it doesn’t stop. I’m in the emergency room, trying to help. I’m at the funeral. Then very easily, the tears come.” Mr. Abaspour said he sometimes pictured Haley “getting lost somewhere, or someone’s going to hurt her. I’m involved and trying to get the guy who did it to stop. Sometimes I kill him. Sometimes it doesn’t get that far.” Other times, he said, he imagines his death, seeing his family “at the funeral home and I’m laying there. I try to see what’s going on at home, how Meggie’s reacting to my death, how Haley’s reacting, what Christine is going through.” He rehashes things Haley has said, like wanting to “start over” or her question: “When I get really old, can I come back home? Will you be there?” He wonders if his worrying laid genetic groundwork for Haley’s illness, “if I’m the cause of what Haley’s going through.” Until recently, Mr. Abaspour, who also has trouble sleeping, told no one about his agonizing thoughts, not even his wife. “I didn’t want to burden her,” he said. “I can handle it. So what if I’m driving to work and I cry? So what if I only sleep for four hours?” But last spring, the family’s therapist noticed “I had certain problems,” he recalled. She encouraged him to tell his wife whenever he had disturbing thoughts. Mr. Abaspour said he hoped that confronting his own anxiety would help “get to the bottom of what Haley’s going through.” He added, “It doesn’t matter for me, but for Haley.” Families once kept illnesses like Haley’s quiet, afraid of being shunned or disparaged. Public acceptance has grown, but some misperceptions and prejudice remain, and families feel conflicted: they want people to understand so the child can get appropriate help, but they also fear that Haley will be mocked or ostracized. “If they keep it a secret then they’re bad parents,” Dr. Elliott said. “If they start spewing diagnoses, they’re subject to criticism because they’re not taking responsibility, just laying it on the illness. Or they’re social pariahs because there are some people who think that mental illness is contagious.” Like other families, the Abaspours sometimes hesitate to publicly label their daughter mentally ill. But they also want people to know, and they get frustrated if people do not fully accept or understand it, or see her symptoms “as a manipulative thing, or they feel like they can fix it themselves, maybe by distracting her,” Ms. Abaspour said. Her own family now understands and is very supportive, but it took some convincing, she said. “My mother would say, ‘She’ll be fine, she’ll be fine, there’s nothing wrong with her,’ ” Ms. Abaspour said. “My sister says, ‘Well, she didn’t act like that when she was over here.’ ” Mr. Abaspour has not told most of his family, who live in England, because they might worry excessively or not understand. He told his sister, but “she was like I was when I first encountered the situation — disbelief or denial,” he said. His sister, he said, has not told her husband or her 20-year-old son, which created an odd atmosphere when they visited the Abaspours in August. “When Haley did have one of her little episodes, they were all like, ‘oh, oh,’ and they wondered why we weren’t running over to her,” Ms. Abaspour said. “I would like to talk to them more about it. If she had diabetes, they’d know she had diabetes.” When, after reading a book for children with bipolar disorder, Haley said, “I can’t wait to go to school and tell everybody I’m bipolar,” the Abaspours were torn. They discouraged her from announcing the diagnosis. But Haley did tell her classmates, “ ‘I have a lot of noise going on in my head and sometimes I feel anxious and sometimes I have to take a walk.’ ” Some day, the Abaspours hope, Haley will have more effective drugs and better coping skills, and society will be more tolerant, so she can lead an independent life. But they have no illusions. “This is not going away,” Ms. Abaspour said. Not for Haley or her family. “The overflow of what Haley has is what has made all of us what we are today.” Pam Belluck PLYMOUTH, Mass. NY Times October 22, 2006 |

On Smartphones, click on the above form and enter your blog in the "COMMENT" section.

Archives

June 2014

CategoriesAll Child Psychology Consciousness Development Dreams Ego Fixation Freud Fromm Hillman Hyperactivity Incest Individuation Intellect Jung Books Articles Mandala Self Spirit Taoism The Four Functions Unconscious Visions Seminar Word Association Test Working With Images |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed